As Famous Churches Seek To Sell Air Rights, The City Demands Its Cut

As the number of churches in the archdiocese drops every year, and as attendance, staff and funds drop to record lows, NYC religious institutions are finding it harder and harder to keep their claims on their land, or to fund the costly upkeep of their historic structures. Those that do—such as St. Patrick’s Cathedral, which unveiled a $177M renovation—are often called out for spending wastefully.

Desperate churches and synagogues have realized their “land-rich, cash-poor” situation and closed their doors for good, moving to more affordable sites and selling their lands to developers. In fact, dozens of churches across Brooklyn sold their sites to make way for luxury residential buildings, high-end apartments or affordable housing units.

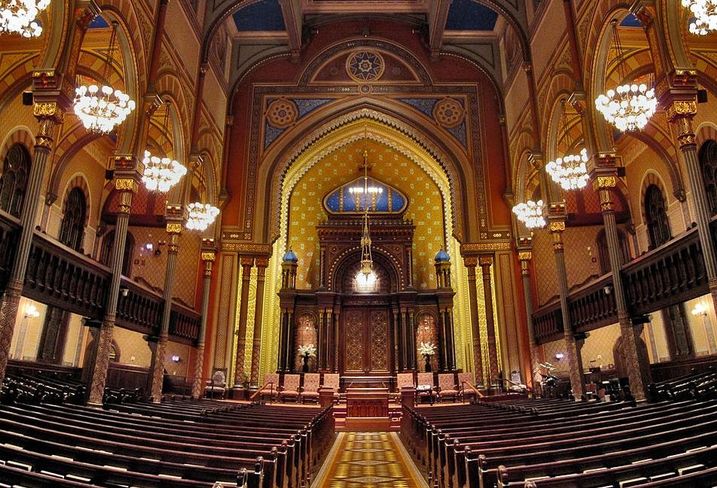

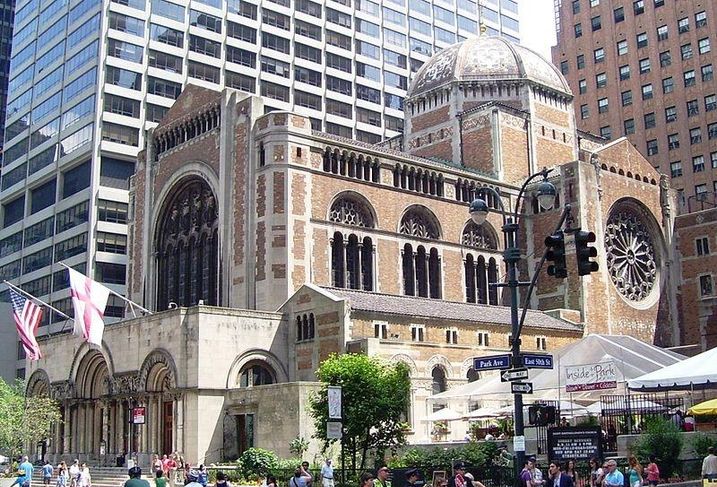

But other houses of worship—like St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Saint Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church and Central Synagogue—aren’t as willing to close their doors. In order stay afloat, these institutions have long considered how they could best leverage their air rights. But the situation isn't as simple as they hoped, and the city is demanding its cut.

Air Right Appeal

For decades, property owners who didn't build to the maximum allowed by zoning regulations were entitled to sell the difference to sites adjacent to them. Although this comes with the cost of never being allowed to build upward themselves, this hardly affects the centuries-old religious structures. And with St. Patrick’s alone having roughly 1.17 M SF of available development rights—“enough space to erect a structure about the size of the Chrysler Building on top of the cathedral”—each institution could stand to make millions (and possibly billions) of dollars.

There has been some precedent of churches selling their air rights before. In 2007, Houston-based developer Hines paid St. Thomas Episocopal Church (pictured) $22M for 275k SF of air rights, which were then used for the construction of the Jean Nouvel-designed MoMA tower.

What’s the Hold Up?

The problem comes from the laws regarding air rights for designated landmarks, which limits the sale of air rights to properties adjacent or across from the landmark. Surrounded by buildings already built to maximum zoning capacity, St. Patrick’s, St. Bartholomew’s and Central have limited options when it comes to finding a legal buyer.

Furthermore, these landmark air rights deals can only be done after a formal city and City Council review process, a burden that few developers wish to take on. Only 10 landmark air rights deals have been done in the last few decades, while hundreds of other development-rights transfers not involving landmark air rights took place under less stringent rules.

Solving The Problem

That’s why the three Midtown East holy houses had negotiated to extend the range of eligible receiving sites. Rather than just adjacent properties, the three institutions want to sell their unused air rights to developers with properties several blocks away.

The Archdiocese of New York put its full support behind the proposal, constantly calling for parishioners to fill out pleas to the city to support the proposal and handing out pamphlets addressed to "elected officials," discussing St. Patrick’s history and describing it as "the most famous Catholic Church in the United States and one of the most famous in the world."

“Enabling the archdiocese to sell St. Patrick's air rights,” the pamphlets claim, “would not only safeguard the future of the physical landmark but it would also strengthen the archdiocese's ability to sustain and expand its robust charitable, pastoral and educational programs, which tens of thousands of New Yorkers of all faiths rely upon every day."

There was, of course, resistance to the proposal. While preservationists supported the idea of giving landmark owners a revenue stream to pay for maintenance, they worried the program could “lead to unchecked development and the demolition of worthy older buildings if it isn’t well designed.” This is partly why the original rule change, proposed by then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration, failed so miserably and was eventually dropped.

The Grand Plan

But an interesting development came in June, when the City Planning Commission’s East Midtown Steering Committee studying the development potential of East Midtown created a proposal that would give the institutions the power to sell their air rights anywhere within the district, but with a caveat: the city would take a cut (20% to 40%) of each sale and put it in a public fund dedicated to the improvement of public spaces and transit access throughout the district.

Naturally, the three religious properties weren’t exactly thrilled with the proposal, writing “we are concerned that the high assessment on transfers proposed in the Committee report greatly diminishes the rezoning’s twin objectives of promoting development and historic preservation."

An Outside Analysis

Zetlin & De Chiara partner James Rowland is, on the whole, mixed on the situation and how it’ll play out going forward. What exactly these “improvements” entail, he says, is vague, but he adds that the city “seems to be saying that if the city is going to agree to allow for the sale of air rights/development rights beyond the current law, there should be some public benefit.”

He adds that it seems clear that the Steering Committee’s aware that the sale of development rights is beneficial to both the seller and the buyer, so it’s an easy way to seek payment for the “public good.”

“It appears that the Steering Committee’s position is that St. Patrick’s and the other landmarked religious institutions should not take issue with paying the city its cut because if they're not allowed to sell their air rights within the entire Midtown East zone, they get $0, as opposed to receiving 60% and 80% of a number that is way more than $0," James explains.

As for the preservation groups, James says he understands these groups lobbied for the Steering Committee to exclude the religious institutions from the 20% to 40%, understanding that having sufficient funds to restore and maintain the landmarked buildings was important, but the Committee has decided to treat everyone, both private developers and the owners of landmarks (who are already severely restricted in the use of their property) and religious institutions the same.

But what about the institutions themselves? Won’t they be getting a raw deal, being forced to pay the city in order to survive? As a religious man, James says there is part of him that is torn about the city’s decision, but the decision truly rests in the hands of the City Council.

“I believe that there will be a fight when the proposal comes before the City Council,” he says. “They can ultimately decide to apply the 20% to 40% to all or make an exception for religious institutions.”

To learn more about our Bisnow partner, click here.